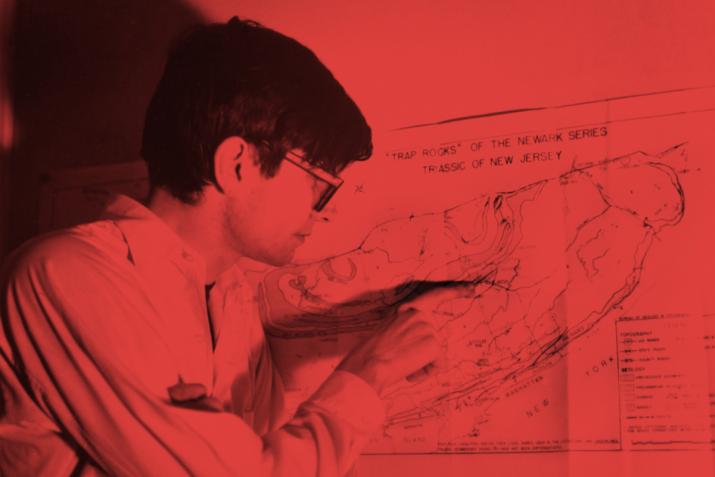

Abstract Cartography

We are very pleased to announce the exhibition Robert Smithson: Abstract Cartography launches this summer at Marian Goodman Gallery New York, open from June 24 to August 20, 2021.

Robert Smithson, Dallas-Fort Worth Regional Airport Layout Plan: Wandering Earth Mounds and Gravel Paths (1966)

Graphite and crayon on paper

11 x 14 in. (27.9 x 35.6 cm)

©Holt/Smithson Foundation, Licensed by VAGA at ARS, New York

Robert Smithson, Dallas-Fort Worth Regional Airport Layout Plan: Wandering Earth Mounds and Gravel Paths (1966)

Graphite and crayon on paper

11 x 14 in. (27.9 x 35.6 cm)

©Holt/Smithson Foundation, Licensed by VAGA at ARS, New York

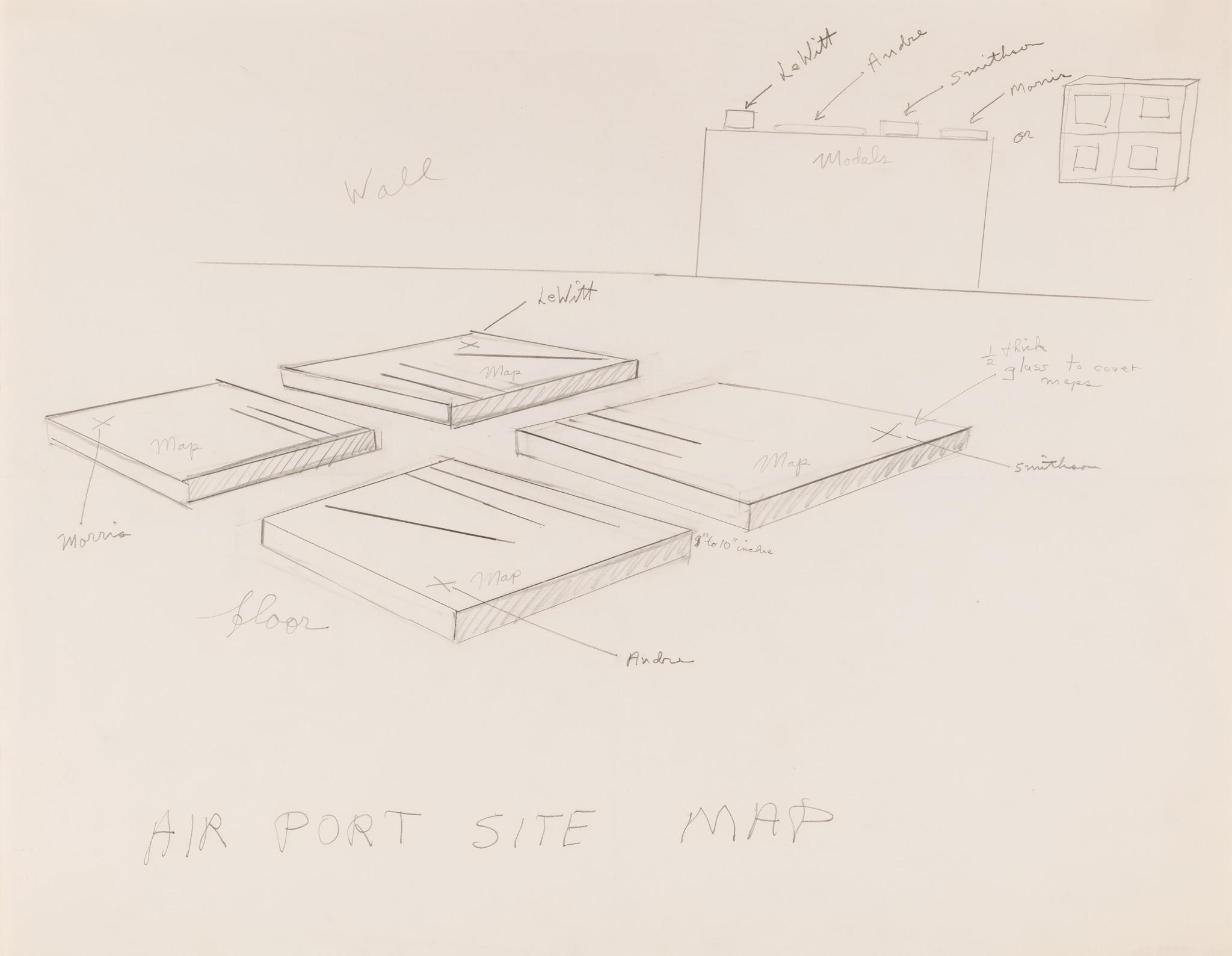

Robert Smithson, Airport Site Map (c.1967)

Graphite on paper

19 x 24 in. (48.3 x 61 cm)

Collection of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Gift of the Estate of Robert Smithson

©Holt/Smithson Foundation, Licensed by VAGA at ARS, New York

Robert Smithson, Airport Site Map (c.1967)

Graphite on paper

19 x 24 in. (48.3 x 61 cm)

Collection of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Gift of the Estate of Robert Smithson

©Holt/Smithson Foundation, Licensed by VAGA at ARS, New York

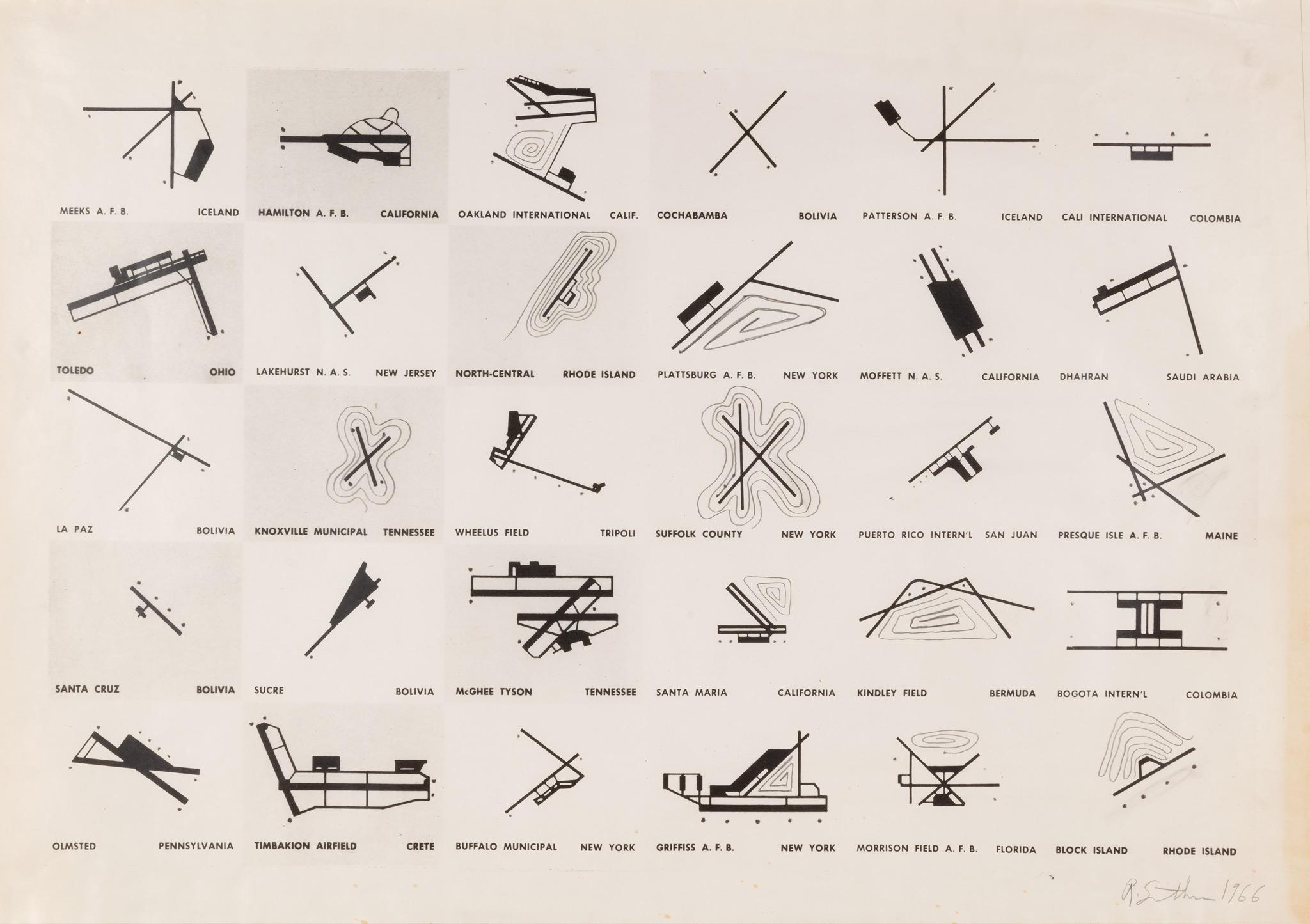

Robert Smithson, Texas Airport (1966)

Graphite on photostat

17 1/2 x 27 3/8 in. (44.5 x 69.5 cm)

Collection of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Gift of the Estate of Robert Smithson

©Holt/Smithson Foundation, Licensed by VAGA at ARS, New York

Robert Smithson, Texas Airport (1966)

Graphite on photostat

17 1/2 x 27 3/8 in. (44.5 x 69.5 cm)

Collection of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Gift of the Estate of Robert Smithson

©Holt/Smithson Foundation, Licensed by VAGA at ARS, New York

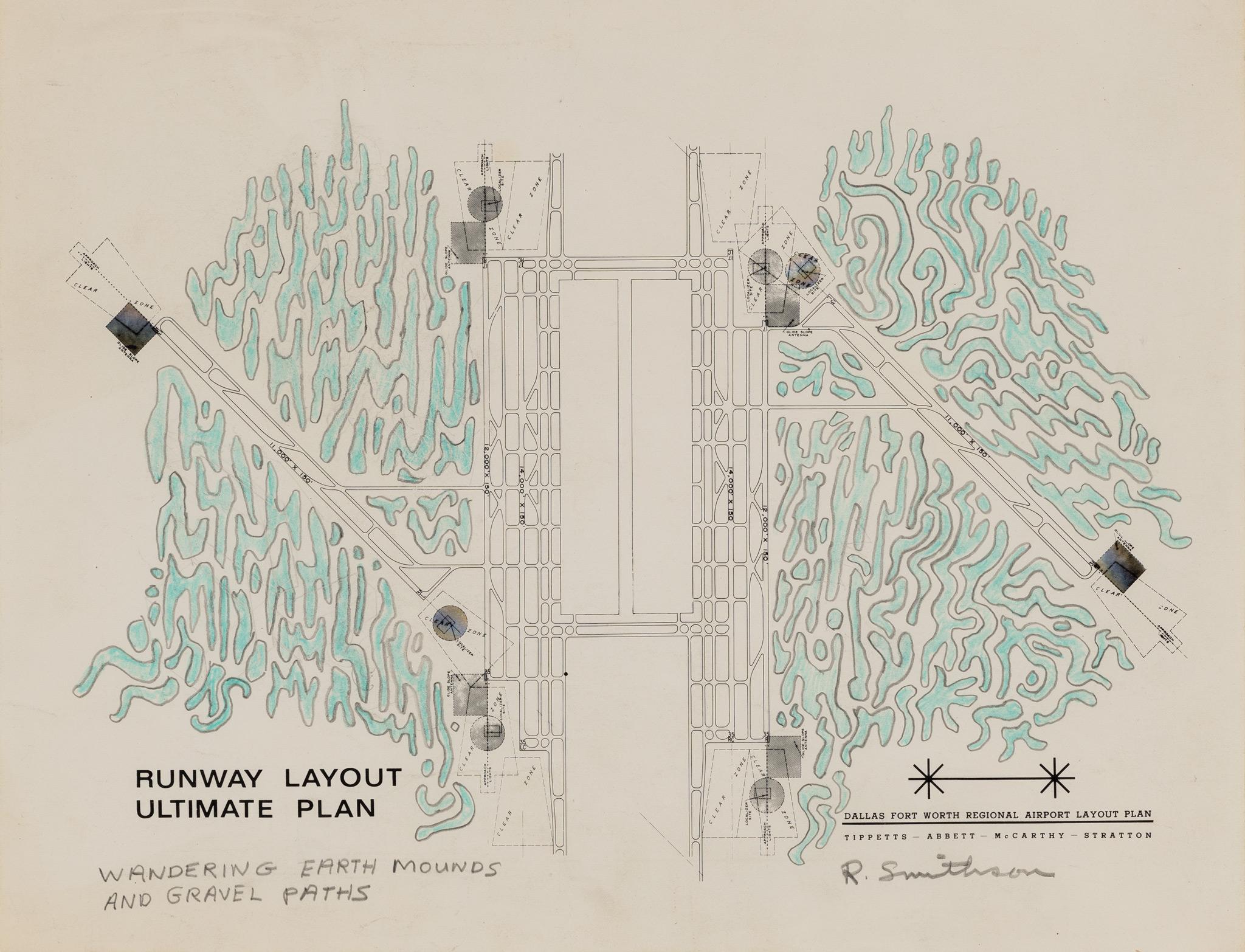

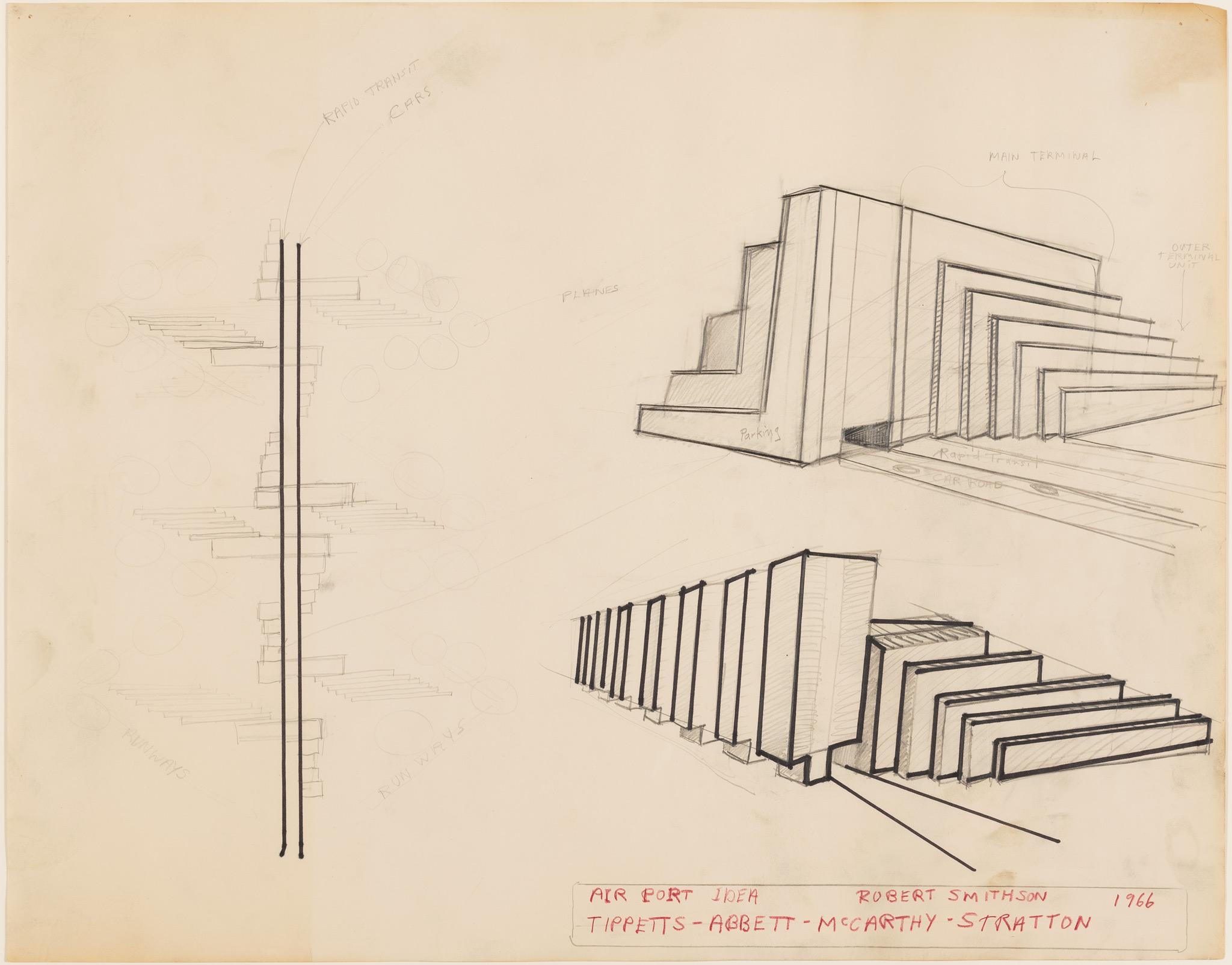

Robert Smithson, Airport Idea [Tippetts, Abbett, McCarthy, Stratton] (1966)

Ink, graphite, and colored pencil on paper

19 x 24 in. (48.3 x 61 cm)

©Holt/Smithson Foundation, Licensed by VAGA at ARS, New York

Robert Smithson, Airport Idea [Tippetts, Abbett, McCarthy, Stratton] (1966)

Ink, graphite, and colored pencil on paper

19 x 24 in. (48.3 x 61 cm)

©Holt/Smithson Foundation, Licensed by VAGA at ARS, New York

Proposals for the Dallas-Fort Worth Regional Airport (Tippetts—Abbett—McCarthy—Stratton, Architects and Engineers)

Art today is no longer an architectural afterthought, or an object to attach to a building after it is finished, but rather a total engagement with the building process from the ground up and from the sky down. The old landscape of naturalism and realism is being replaced by the new landscape of abstraction and artifice.

How art should be installed in and around an airport makes one conscious of this new landscape. Just as our satellites explore and chart the moon and the planets, so might the artist explore the unknown sites that surround our airports.

The future air terminal exists both in terms of mind and thing. It suggests the infinite in a finite way. The straight lines of landing fields and runways bring into existence a perception of “perspective” that evades all our conceptions of nature. The naturalism of seventeeth-, eighteenth- and nineteenth- century art is replaced by non-objective sense of site. The landscape begins to look more like a three dimensional map than a rustic garden. Aerial photography and air transportation bring into view the surface features of this shifting world of perspectives. The rational structures of buildings disappear into irrational disguises and are pitched into optical illusions. The world seen from the air is abstract and illusive. From the window of an airplane one can see drastic changes of scale, as one ascends and descends. The effect takes one from the dazzling to the monotonous in a short space of time—from the shrinking terminal to the obstructing clouds.

Below this concatenation of aerial perceptions is the conception of the air terminal itself, firmly rooted in the earth. The principal runways and series of terminals will extend from 11,000 feet to 14,000 feet, or about the length of Central Park. The outer limits of the terminal could be brought into consciousness by a type of art, which I will call aerial art, that could be seen from aircraft on takeoff and landing, or not seen at all.

On the boundaries of the taxiways, runways or approach “clear zones” we might construct “earthworks” or grid type frameworks close to the ground level. These aerial sites would not only be visible from arriving and departing aircraft, but they would also define the terminal's manmade perimeters in terms of landscaping.

The terminal complex might include a gallery (or aerial museum) that would provide visual information about where these aerial sites are situated. Diagrams, maps, photographs, and movies of the projects under construction could be exhibited—thus the terminal complex and its entire airfield site would expand its meaning from the central spaces of the terminal itself to the edges of the air fields.

Letters A, B, C, and D (see aerial map) stand for installations of art on the margins of the main terminal complex. This art is remote from the eye of the viewer the way a galaxy is remote from the earth. In fact, the entire air terminal may be considered conceptually as an artificial universe, and as everyone knows, everything in the known universe isn't entirely visible. There is no reason why one shouldn't look at art through a telescope. Our terminal universe is built in the shape of a rectangle with two diagonals set in a photo firmament of haze and non-objective land masses. The double white rectangles within the grid shall someday contain a series of terminals each one the size of Grand Central Station. At the moment we are considering this air terminal through the camera obscura of our mind—the camera takes a picture but does not see it. “Some ideas are logical in conception” says Sol LeWitt, “and illogical perceptually.” Visibility is often marked by both mental and atmospheric turbidity. Just how we should look at art is a question that is rarely considered. Simply looking at art at eye-level is no solution. If we consider the aerial map as "a thing in itself," we will notice the affects of scattered light and weak tone reproduction. High-altitude aerial photography shows us how little there is to see, and seems to prove what Lewis Carroll once said, “They say that we Photographers are a blind race at best.” Carl Andre sees the camera as the most catastrophic invention of the Modern Age.

Aerial art can therefore not only give limits to “space,” but also the hidden dimensions of “time” apart from natural duration—an artificial time that can suggest galactic distance here on earth. Its focus on “non-visual” space and time begins to shape an esthetic based on the airport as an idea, and not simply as a mode of transportation. This airport is but a dot in the vast infinity of universes, an imperceptible point in a cosmic immensity, a speck in an impenetrable nowhere—aerial art reflects to a degree this vastness.

A. ROBERT MORRIS

His proposal is an “earth mound” circular in shape and trapezoidal in cross section. Its surface would be sod, and its radius might be extended as much as a thousand feet—easily viewed from arriving and departing aircraft.

B. CARL ANDRE

A crater formed by a one-ton bomb dropped from 10,000 feet.

or

An acre of blue-bonnets (state flowers of Texas).

C. ROBERT SMITHSON

A progression of triangular concrete pavements that would result in a spiral effect. This could be built as large as the site would allow, and could be seen from approaching and departing aircraft.

D. SOL LEWITT

His proposal is “non-visual” and involves the substratum of the site. He emphasizes the “concept” of art rather than the “object” that results from its practice. The precise spot in the site would not be revealed—and would consist of a small cube of unknown contents cast inside a larger cube of concrete. The cube would then be buried in the earth.

Smithson, Robert. "Aerial Art." Studio International, February—April 1969.