Doubling Down: Nancy Holt’s Stone Enclosure: Rock Rings

Circles everywhere! Upon entering Nancy Holt’s 2018 solo exhibition at Dia Art Foundation in Chelsea, New York City the observer is engulfed by a network of flat circular line drawings, round cast shadows, and orbicular light pools. Circles also appear dimensionally: as dark voids cut into walls and as mirrored surfaces shaped into orbs. Very tangibly Holt’s circles telescope out, forming lens-less viewfinders. As one stoops to look through cast-iron spyholes, for example in Dual Locators (1972), a tunneling effect occurs: circles become layered onto circles.

Looking back over Holt’s heterogeneous body of work, one soon realizes that the circle, an ancient symbolic form, is her elemental syntax. This form permeates her Locators, a body of work which includes site-specific works, such as Avignon Locators (2012); videos and films, like Going Around in Circles (1973); and interrelated earthworks, notably, Sun Tunnels (1973-6) and Solar Rotary (1995). Of all her works, it is in Stone Enclosure: Rock Rings (1977-8) where Holt doubles down on her syntax: twice referring to the symbolic signifier in her title, and doubly referencing it in her ring-within-ring design. [Fig. 1] In this site-specific sculpture her circularity extends outward, profoundly binding the site and material she selected to a more cosmic notion of universality — the laws of thermodynamics associated with the expanding universe.

In August 1977 Holt arrived in Bellingham, Washington State to develop an artwork for the campus of Western Washington University. The idea began ecologically, emerging out of her “growing awareness of the lush Northwestern terrain — the ancient mountain rocks, the hazy green hills, the huge fir trees, the heavy wet weather, the rugged seacoast.” 1 Immediately she was attracted to an unruly wooded bluff, then at the very southern isolated edge of Western’s picturesque campus. The site was “a removed, meditative space away from the university buildings” Holt chronicled, “bordered in one direction with tall pines.” 2

After building scale models in her New York studio and constructing a full-size maquette in a nearby on-site pit, Holt finalized the architectural dimensions of Stone Enclosure: Rock Rings: an inner twenty-foot diameter wall nested inside a forty-foot outer wall, each ten feet high and two feet thick. Working with local mason Al Poynter, 3 Holt developed two entry archways in each of the concentric walls. With the help of astronomer Willard Brown and surveyor Bill Dollarhide, she situated four entrances and exits on a ‘true’ north-south axis — calculated from “the North Star, Polaris, in a way similar to that used by Northwest coast navigators in plotting the courses of their ships.” 4 Furthering the nautical theme, Holt punctuated each wall with six portholes, positioning them on cardinal compass points: NE, E, SE, NW, W and SW. Like the archways, the directionally aligned holes cut through the walls, form large ‘viewfinders’ and draw observers inside, “surrounding them and enclosing them,” as she put it, “while giving them views of the landscape through layers of arches and apertures.” 5

Indeed standing in the center of Stone Enclosure: Rock Rings during the day, one looks through aligned portholes and, as with her Locators, a tunneling effect occurs. [Fig. 2] The lens-less holes open up the double-wall enclosure to reveal focused viewpoints in the landscape beyond. By contrast, when moving to the outside and looking in, one’s perception of dimensionality fluctuates. Depending on the shifting sunlight, space either telescopes out or becomes flat, causing the viewer, as Holt noted, to question their “orientation in space.” 6 [Fig. 3] Spatial perception, as it turns out, is a key factor in her elemental syntax, giving way to a deeper understanding of circularity.

Circles are ancient symbols that stand for unity, universality, and circularity — the cycle of seasons, the progression of life. Or, as Holt puts it, circles and, by extension tunnels, symbolize “birth, death, or just transition in general.” 7 More importantly, concentric circles have a broader significance. In astrophysics, the design represents planetary relationships within our solar system; for millennia it is how we picture the clockwork mechanism of orbs rotating around the sun. While fundamentally Holt’s ring-within-ring constellation enantiomorphically 8 rhymes with the Empyrean pattern of the cosmos, the piece is doubly tuned to more scientific notions of space-time.

At night, standing in the center, darkness blots out the distant landscape. Instead of gazing horizontally out, one looks up. Holt’s rings become a single large porthole, framing the night sky. At that moment the aligned archways become a pointing device, tuned directionally to Polaris, the more-or-less stationary Pole Star of the night sky. As the night progresses the other stars rotate, pivoting around Polaris and making a full circle every twenty-four hours or so. 9 Many photographers, using long-exposure photography have documented these rotating stars’ concentric light trails, recording the galactic clock mechanism of the night sky. The slotted archway of Stone Enclosure: Rock Rings also marks time. It captures segmented sections of the solar clock mechanism and, in a fundamental way, connects space and time or, as physicists since Albert Einstein call it, space-time. Space-time, however, resonates even more deeply within the very fabric of the work.

Holt specifically chose a local brown stone that was quarried from the shores of Harrison Lake in British Columbia, Canada, about sixty-five miles north of the site. She was particularly attracted to the roughly hewn metamorphic stone, which dates back to the dinosaur era, the Triassic period. This distinctive 200 to 230-million-year-old primordial schist rock is formed, “without melting … having spent some time deep in the crust of the Earth.” 10 As a result, it splits apart fairly easily, though rarely regularly, producing a rough, irregular finish.

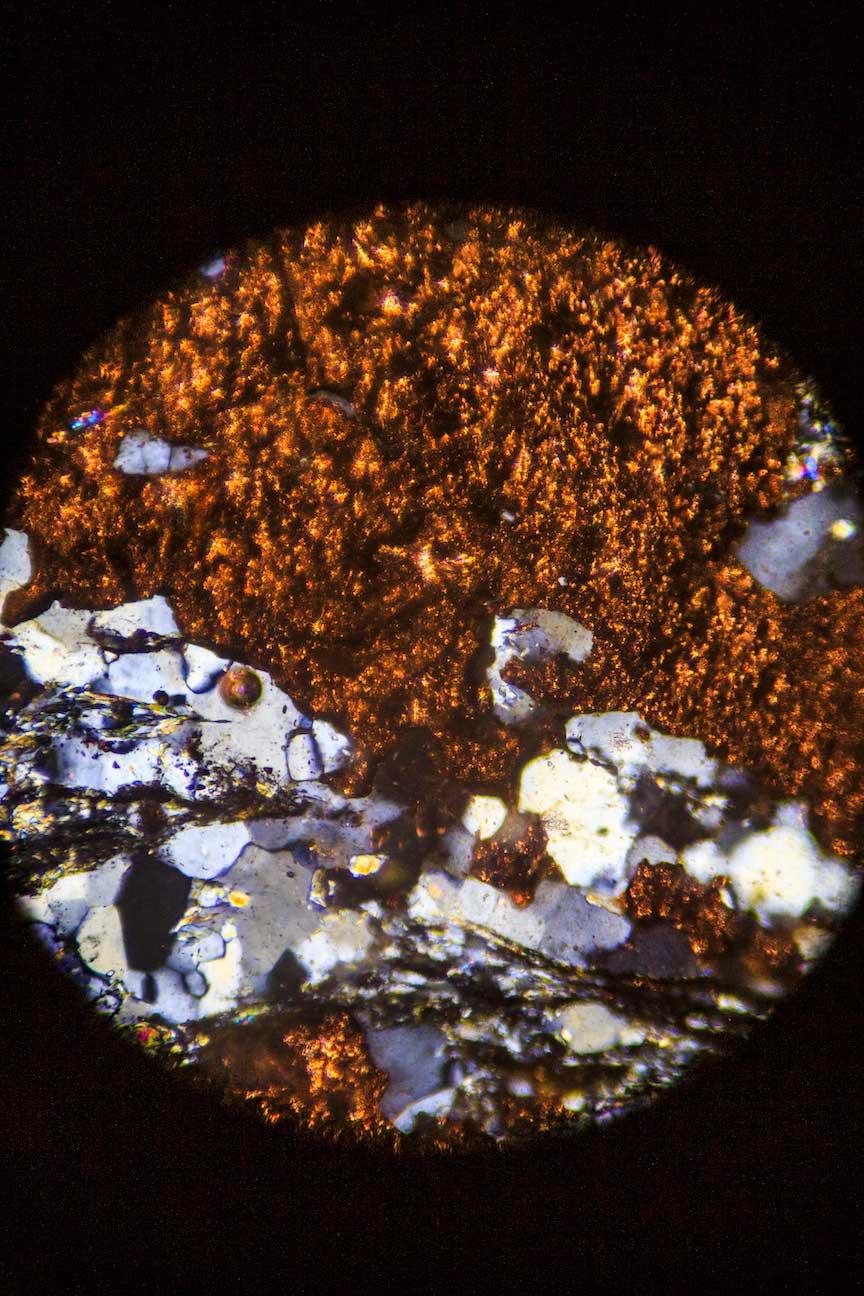

George Mustoe, now retired Western Washington University geologist, met with Holt in the 1970s and conducted microscopic analysis of the schist used in Stone Enclosure: Rock Rings. In a recent and more in-depth study, Mustoe found that the reddish wash covering parts of the piece is the result of large amounts of iron pyrite (iron sulfide) compressed into the stone. He notes how “under moist atmospheric conditions, pyrite transforms to reddish iron oxides” 11 drawing it out of the stone and ultimately weakening its composition. [Fig. 4] Though Holt spoke of the work as having a “raw permanence” 12 (the work is still intact and in excellent condition), chemical analyses reveal Stone Enclosure: Rock Rings has an internally sped-up clock. Encoded within its chemical make-up is a profound sense of entropy, whereby the work will rapidly decompose. The circularity of Holt’s work is in sync with an irreversible and rapid sense of universal disorder, in which randomness increases. As James Gleick explains, as our cosmos expands, entropy grows; Holt’s sculpture resonates with the snowballing chaos of our universe. Like the cosmos, it is moving from a highly ordered or stable state to “an irreversible process…connected with the growth of entropy” 13 - what Gleick calls the “cosmic mystery”. 14

This was a very personal and important work for Holt. She described that she had an incredibly “strong need to make” Stone Enclosure Rock Rings, believing the work accomplished something deep within her “psyche.” 15 On a nightly basis the work manifests Holt’s interest in “naked-eye” solar observations; the “need,” as she put it, “to look at the sky — at the moon and stars — is very basic, and it is inside all of us.” 16 Her desire was to “make people conscious of the cyclical time of the universe — the daily axial rotation of our planet Earth and its annual orbit around the Sun.” 17 As it turns out, her sense of profundity unleashes a more profound cascade of interconnected rhythmic vibrations. A ‘low-level’ tremor emerges from the concentric form and, if one stays for a duration, this vibration develops into a cyclone, encircling and engulfing the viewer. Observers not only see but also experience the cyclical space-time and become connected to the vastness of outer space.

Bibliography

Gleick, James. Time Travel: A History. New York: Pantheon Books, 2016.

Hatch, John G. ”Modern Earthworks and Their Cosmic Embrace,” ASP Conference Series, vol. 441, (2011): 225-33.

Holt, Nancy. Keynote Lecture at Princeton University Art Museum, October 5, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hRNeN9Y1YQo [accessed May 22, 2019].

Marter, Joan. “Systems: A conversation with Nancy Holt,” Sculpture Magazine vol. 32, no. 8 (October, 2013): 28-33.

Saad-Cook, Janet with Charles Ross, Nancy Holt and James Turrell, “Touching the Sky: Artworks Using Natural Phenomena, Earth, Sky and Connections to Astronomy,” Leonardo vol. 21, no. 2 (1988): 123-34.

Tufnell, Ben and Matt Watkins (editors). Nancy Holt: Locators. London: Parafin, 2015.

Williams, Alena J., ed. Nancy Holt: Sightlines. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2011.

About the Author

Barbara L. Miller is a teacher, artist-photographer and curator, working in the Department of Art and Art History at Western Washington University. At Western she teaches a variety of innovative, cross-disciplinary courses on ecology, new media, feminism, and postmodernism. She has published on modern and contemporary art, including ‘Trans-dimensional Space: from Moholy-Nagy to Doctor Who’ in Leonardo Journal: Art, Science and Technology (April 2019); ‘’Apoleptic’ Ironies and ’Accident-ed’ Realities: WWI and Berlin Dada Photomontage’ in Dada/Surrealism special issue: “Dada, War, and Peace” (October 2018); and ‘He’ Had Me at Blue: Color Theory and Visual Art’ in Leonardo Journal: Art, Science and Technology, vol. 47, no. 5 (October, 2014). Following her interests in the connections between art, science, technology, ecology, and astronomy Miller has curated the exhibitions Nothing to Say: Sharron Antholt (Western Washington University Gallery, 2019), Surge (Museum of Northwest Art, 2015) and ColorMAD (Western Gallery, 2012). With Dimitri Katsaros, she has presented her photographic works in the exhibitions A Collection of Carefully Curated Images Solar Eclipse, August 21, 2017, Masras OR; Sun (and Moon) at Artist Point, Mt. Baker, October 15, 2018; in the group exhibition Surge at the MoNA (2018-9); and in the solo exhibition Look. the Jansen Art Center, Lynden WA, (2017).

- 1Nancy Holt “Stone Enclosure: Rock Rings” in Nancy Holt: Sightlines, ed. Alena J. Williams (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2011), 92.

- 2Nancy Holt “Artist Statement” reprinted in Sarah Clark-Langager, Sculpture in Place: a Campus as Site (Bellingham, WA: Western Washington University, 2002), 32. Today the site is not so remote. Though the tall pines are still there, the University has built a number of new structures, including the Academic Instructional Center (2009), which sits a few yards away from Holt’s piece and almost, but not quite, occludes the sightline to the Pole Star.

- 3Nancy Holt “Artist Statement” reprinted in Sarah Clark-Langager, Sculpture in Place: a Campus as Site (Bellingham, WA: Western Washington University, 2002), 32. Today the site is not so remote. Though the tall pines are still there, the University has built a number of new structures, including the Academic Instructional Center (2009), which sits a few yards away from Holt’s piece and almost, but not quite, occludes the sightline to the Pole Star.

- 4Nancy Holt “Artist Statement” reprinted in Sarah Clark-Langager, Sculpture in Place: a Campus as Site (Bellingham, WA: Western Washington University, 2002), 32. Today the site is not so remote. Though the tall pines are still there, the University has built a number of new structures, including the Academic Instructional Center (2009), which sits a few yards away from Holt’s piece and almost, but not quite, occludes the sightline to the Pole Star.

- 5Nancy Holt “Artist Statement” reprinted in Sarah Clark-Langager, Sculpture in Place: a Campus as Site (Bellingham, WA: Western Washington University, 2002), 32. Today the site is not so remote. Though the tall pines are still there, the University has built a number of new structures, including the Academic Instructional Center (2009), which sits a few yards away from Holt’s piece and almost, but not quite, occludes the sightline to the Pole Star.

- 6Nancy Holt “Artist Statement” reprinted in Sarah Clark-Langager, Sculpture in Place: a Campus as Site (Bellingham, WA: Western Washington University, 2002), 32. Today the site is not so remote. Though the tall pines are still there, the University has built a number of new structures, including the Academic Instructional Center (2009), which sits a few yards away from Holt’s piece and almost, but not quite, occludes the sightline to the Pole Star.

- 7James Meyer, “Interview with Nancy Holt,” Nancy Holt: Sightlines, ed. Alena J. Williams (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2011), 229.

- 8The term enantiomorphic refers to mirrored relationships such as left- and right-handed gloves.

- 9Astronomers point out that the cosmic clock mechanism, Earth’s rotation in relation to the stars instead of the sun, has a slightly different gyration; it loses four minutes every twenty-four hours. “A sidereal day, or star day, is about 23 hours and 56 minutes.” Howard Schneider et al, Backyard Guide to the Night Sky (Washington, DC: National Geographic, 2009), 21.

- 10Nancy Holt, “Stone Enclosure: Rock Rings,” in Nancy Holt: Sightlines, ed. Alena J. Williams (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2011), 92-96.

- 11Author email correspondence with Mustoe; March 16, 2019.

- 12Holt, “Stone Enclosure: Rock Rings: 1977-78,” reprinted in Nancy Holt: Sightlines, 99.

- 13James Gleick, Time Travel: A History (NY: Pantheon Books, 2016), 119-20.

- 14James Gleick, Time Travel: A History (NY: Pantheon Books, 2016), 120.

- 15Nancy Holt, archived interview (conducted by undocumented interviewers, who most likely include Larry Hanson who originally invited Holt to campus in the 1970s), Western Gallery, Western Washington University, May 20, 1991.

- 16Janet Saad-Cook, Charles Ross, Nancy Holt and James Turrell, “Touching the Sky,” Leonardo, Vol. 21, No. 2, 1988: 128.

- 17James Meyer, “Interview with Nancy Holt,” Nancy Holt: Sightlines, ed. Alena J. Williams (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2011), 227-229.

Miller, Barbara. “Doubling Down: Nancy Holt’s Stone Enclosure: Rock Rings.” HOLT/SMITHSON FOUNDATION, June 2019. https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/doubling-down-nancy-holts-stone-enclosure-rock-rings.