Robert Smithson, "A Nonsite (Franklin, New Jersey)" (1968)

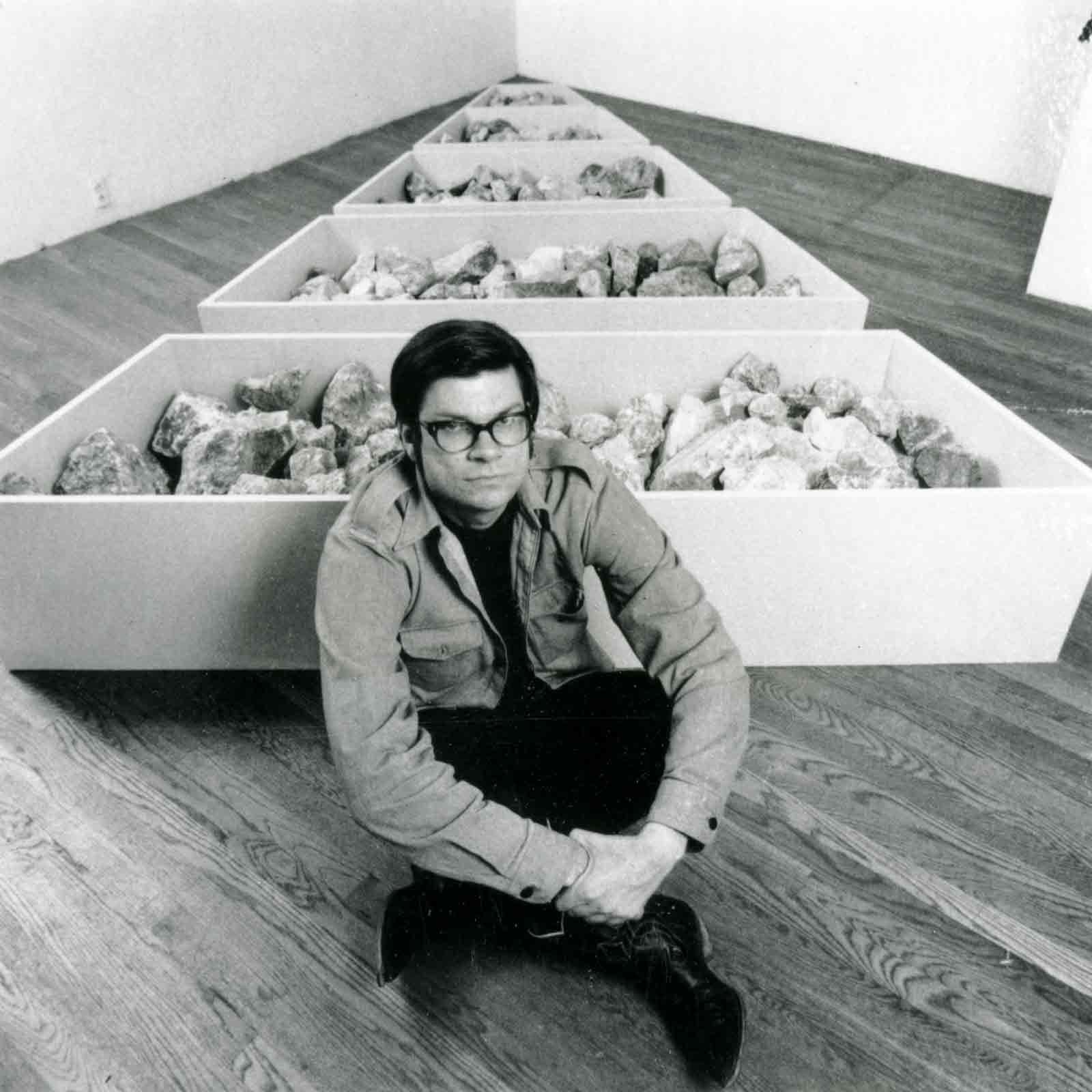

In 1968, Robert Smithson realized an important group of works he collectively called Nonsites. This series features bin-like structures in which the artist deposited rocks, sand, broken concrete, and other elements he collected at various sites in New Jersey. Accompanying these sculptures, Smithson hung on gallery walls photographs he’d snapped at the same Garden State locations, as well as fragments of maps that could lead other people to these places. He repeatedly declared that where he had gathered his materials—whether it was the Pine Barrens, Franklin, Bayonne, or Edgewater—was as much a part of the experience of his endeavor as the freestanding, seemingly independent work. As Smithson explained in 1970, “…my art exists in two realms—in my outdoor sites which can be visited only and which have no objects imposed on them, and indoors, where objects do exist…” 1 In other words, though they were never seen together, his Nonsites and the actual Sites complete one another.

A Nonsite (Franklin, New Jersey) was the third work of this type that Smithson created. It touches upon an unlikely range of themes, including time travel, geology, the American highway system, big business, a hobby pursued by rock hounds, and growing up in New Jersey. As early as November 1970, critic John Perreault astutely observed, “Now what I have always liked about Smithson’s ‘Non-sites’ [sic.] is that these geometrical bins of rocks and his maps and Instamatic photos and other data have never been strictly documentational. Smithson’s vision is too complicated and perhaps too dark to be content with one-to-one relationships.” 2

The artist’s sculptures and photographs have frequently been discussed in terms of his interest in futuristic science fiction novels, whether applicable or not. This Nonsite, originating in a short day trip to Franklin, New Jersey, instead thrusts gallerygoers backwards, to an earlier period when railroad tracks ran directly to the once thriving quarry to which Smithson journeyed with colleagues. After transporting tons of zinc and iron ore from there (to be used for industrial purposes), trains to this site ceased operations after World War II; the tracks were only removed in 1966.

If you go to Franklin today, the two-lane, undivided road that brings you there looks much the way it did on June 14, 1968, when Smithson, Nancy Holt, and Michael Heizer drove to the Franklin Mineral Museum. Though plans were filed several times, Route 23, the final leg of the trip, was never upgraded into a freeway. Consequently, the surrounding, rural area seems frozen in time. You’d never suspect that a bustling metropolis like New York is only forty-five miles away.

Smithson went to Franklin for a number of reasons. Chief among them, he wrote in May 1968, was the access he would have to “an abundance of broken rock.” 3 He also was pleased, he noted, that he would be finding minerals that, when placed under ultraviolet lights, glowed either red (calcite) or green (willemite). Even though what he assembled would never be exhibited in a way that would reveal their true natures—a mercury vapor type lamp would be needed to achieve that—he was aware that he was approximating a palette associated with Impressionism. Shortly before she died in 2014, Nancy Holt referred to this aspect of this Nonsite as “the secret of the rocks.” 4

Surprisingly, no one seems to have ever investigated whether any of the rocks Smithson brought together are red or green. Before he purchased them, did he check to see if they were colored, using the lights provided at the former quarry? In the five bins he constructed, were green minerals separated from red ones? While countless art historians have analyzed A Nonsite (Franklin, New Jersey), geologists have not.

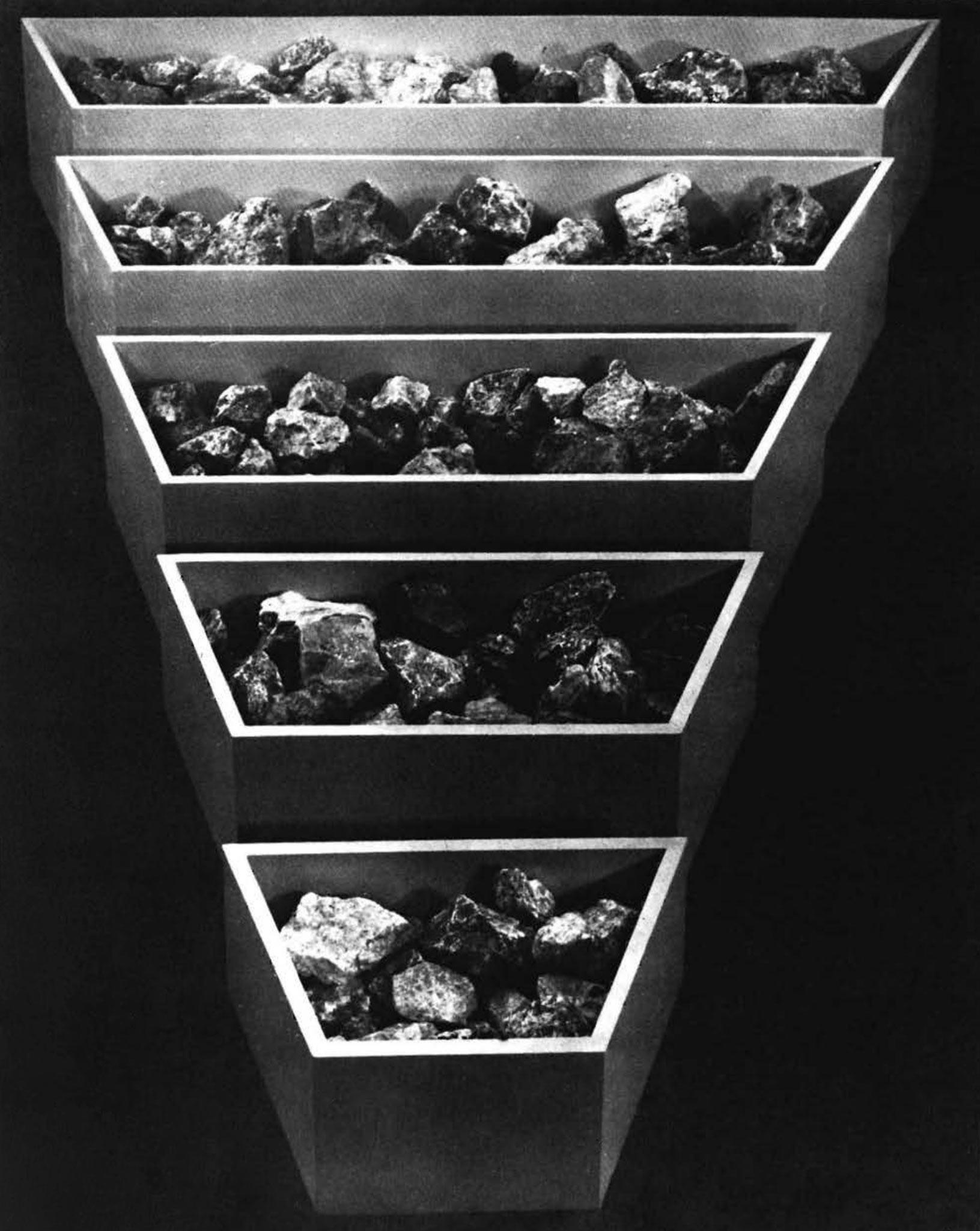

By the time Smithson exhibited his sculpture in the landmark Earthworks exhibition held at the Dwan Gallery during October 1968, a show he helped organize, it was comprised of five—not the initially planned six—trapezoidal wood bins. They were painted a neutral cream color, and rested directly on the floor, by then, a commonplace feature of contemporary sculpture. In addition, on a nearby wall, the assemblage was accompanied by a framed and mounted on mat board birds’ eye view of the Franklin site divided into five segments. Their wedge-like divisions echoed the shape of the bins. Yet, the five wood containers and the five-part photograph generally are displayed in reverse order rather than mimicking one another. This has thwarted viewers from noticing that, by designing both the bins and the aerial view so that they diminished in size, the artist relied on classical perspective. Had they reinforced one another, this would have been clearer.

Twenty-five black and white prints framed together as one unit occasionally accompany the bins and the other photograph. These images feature piles of rocks and a cave entrance. And, below the segmented “map” of Franklin, Smithson included an explanatory text. More a gathering of facts than an aesthetic interpretation, he itemized the dimensions of each container and mentioned that more than 140 minerals could be found at the former quarry. “Tours to sites,” the sculptor additionally announced, “are possible.”

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago has owned A Nonsite (Franklin, New Jersey) since 1979. It travels to other museums infrequently. After all, it’s expensive to ship rocks. When the work has travelled to other institutions, their curators, registrars, and/or handlers rearrange the minerals into new patterns because there is no authorized schematic. Some configurations are more compelling than others. More often than not, it appears that whomever is placing the rocks in the wood bins has forgotten that Robert Smithson was an artist who would have positioned everything carefully.

Among the New Jersey Nonsites, subtle differences can be discerned. A learning curve is evident. Still, it’s hard to determine which came first, the proverbial chicken or the egg. When Smithson travelled to a site, did he already have a general idea of the parameters a Nonsite would assume? For example, if you go to the Pine Barrens, shoveling sand into bags might not be the first thing that would come to your mind. Maybe you’d collect branches from the trees that give the area its name. But, it indeed was sand that the artist placed in the first Nonsite’s bins, which, incidentally, were perched on a wide, shaped pedestal. However, focusing on sand does not seem all that remarkable if you consider the role a sandbox had played in The Monuments of Passaic, his photo essay published in the December 1967 issue of Artforum.

Then, too, the sites that correspond to the New Jersey Nonsites were not unfamiliar or neutral places for Smithson. The second Nonsite, which was destroyed after it was exhibited at the Walker Art Center, pinpointed, for example, an area near his childhood home that was as familiar to the artist as the back of his hand. He and his father had often driven along Paterson Plank Road in East Rutherford on their way to and from New York. The sculptor would mention that as a child he visited many quarries in New Jersey: Franklin was one of them. This site was only thirty-five miles from the teenager’s home in Clifton. And then, there’s the fifth Nonsite, whose components were collected not far from Palisades Amusement Park. Is there a teenager raised in North Jersey during the nineteen fifties and sixties who never went there—or heard its catchy jingle constantly played on the radio?

As the Nonsites—and various other artworks—are studied in greater detail, their connections to Robert Smithson’s life and times will probably become clearer.

Bibliography

Robert Hobbs, Robert Smithson: Sculpture, exhibition catalogue, Cornell University Press, 1981.

William R. Klink, “Robert Smithson: New Jersey Artist of the Earth,” New Jersey History, Fall/Winter 1981pp. 183-192.

Robert A. Sobieszek, Robert Smithson: Photo Works, exhibition catalogue, Los Angeles County Museum of Art/University of New Mexico Press, 1993.

Alexander Nagel, "Art Out of Time: The Relic and Robert Smithson," Artforum, v.51, n. 2, October 2012, pp. 233-239

Phyllis Tuchman, Robert Smithson’s New Jersey, exhibition catalogue, Montclair Art Museum, 2014.

About the Author

Phyllis Tuchman is a long time art writer who has published articles, interviews, and reviews in a variety of places, including Artforum, Art News, Town & Country, New York Newsday, and the New York Times. A trained art historian, she has taught at Williams College and lectured at many museums and colleges. Among the exhibitions she has curated are: Six in Bronze, Big little Sculpture, Norte del Sur: Venezuelan Art Today, George Segal, obras de 1959 a 1989, Robert Motherwell, 1944-1951, and Robert Smithson’s New Jersey. Born and raised in Passaic, New Jersey, she knew Robert Smithson and Nancy Holt.

- 1Robert Smithson in “Discussions with Heizer, Oppenheim, Smithson,” Avalanche, Fall 1970

- 2John Perreault, “art: Vicious Circles,” Village Voice, November 12, 1970

- 3Robert Smithson, typed, signed statement, Smithson/Holt papers, Box 4, Archives of American Art

- 4In conversation with the author, December 2014

Tuchman, Phyllis. "Robert Smithson, 'A Nonsite (Franklin, New Jersey)' (1968)." Holt/Smithson Foundation, May 2020. https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/robert-smithson-nonsite-franklin-new-jersey-1968.